3 min

Moths in the Mojave, with UConn's David Wagner

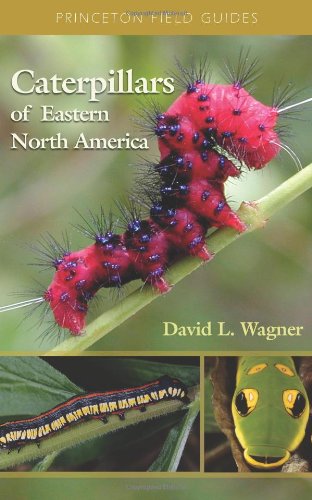

Did you know that there are approximately 180,000 moth and butterfly species living in California’s Mojave Desert? Moths, the winged insects famous for eating sweaters and flocking to lights at night, are a mysterious and captivating species for entomologists like UConn's David Wagner. He was part of a research study that was documented recently in The Washington Post. Each night in the desert, vast clouds of sphinx moths, some spanning the palm of your hand, speed between night-blooming flowers, sipping nectar. Ethmia, tiny black moths with spots shaped like musical notes, emerge from the dark like fairies. Thousands of geometrid moths, no bigger than your fingernail, slip by cloaked in desert hues from rusty reds to pale green. To witness them, I traveled deep into the Mojave Desert this spring with a team from the California Academy of Sciences working to ensure the survival of lepidoptera. For two days, we beat bushes, placed traps and collected thousands of moths to see what lives there — and what can be saved. Moths have inhabited our planet for at least 200 million years. But the conservation status of about 99 percent of moth species remains unknown. Some, like sphinx moths, remain abundant. Many others are probably being pushed to the brink by development, land-use changes, pesticides and pollution, and rising temperatures. “It’s not this unseen force,” says David Wagner, an entomologist at the University of Connecticut. “It’s humans.” Over two nights in the desert, I discovered just how easy it is to fall in love with an unloved insect. And why “mothing” may be the best way to discover the miracle of biodiversity in your own backyard. On the arid western edge of the Mojave, where the desert floor rises to meet the San Bernardino Mountains, sits the 306-acre Burns Piñon Ridge Reserve. We venture out in the morning with beating sticks. Hitting the branches of small oaks and rabbitbrush deposits a treasure trove of insect life into collectors made out of fabric: Crane flies, green lacewings, spiders, walking sticks and caterpillars that will one day grow into moths. Wagner and Chris Grinter, an entomologist and collection manager at the California Academy of Sciences, will catalogue the most interesting ones. The academy houses a collection of 18 million insects, 700,000 of which are butterflies and moth specimens. Many are still waiting for scientists to identify and name them. The plight of moths and caterpillars has fascinated Wagner since childhood. After 20 years, he is no less enthusiastic — or worried. Wagner traveled to Burns Piñon to help finish his magnum opus, the successor to his 500-page guide to eastern North America’s caterpillars. The guide for the west will probably run more than 1,500 pages, a testament to the region’s remarkable biodiversity. As the sun sets, the mood is anticipatory. We head out into the desert to set our traps and see what moths we’ll discover. “The nice thing,” says Grinter, “is moths will come to you.” The article is an amazing read and the link is above. And if you are interested in knowing more about moths, insects, or the fascinating field of entomology, then let us help. Dr. David Wagner is an expert in caterpillars, butterflies, moths, and insect conservation, and he's commented extensively on the current decline of insects worldwide. Click his icon to arrange an interview today.