3 min

Villanova's Héctor Varela Rios, PhD, Comments on Bad Bunny's Super Bowl Performance, "Unapologetic" Swagger

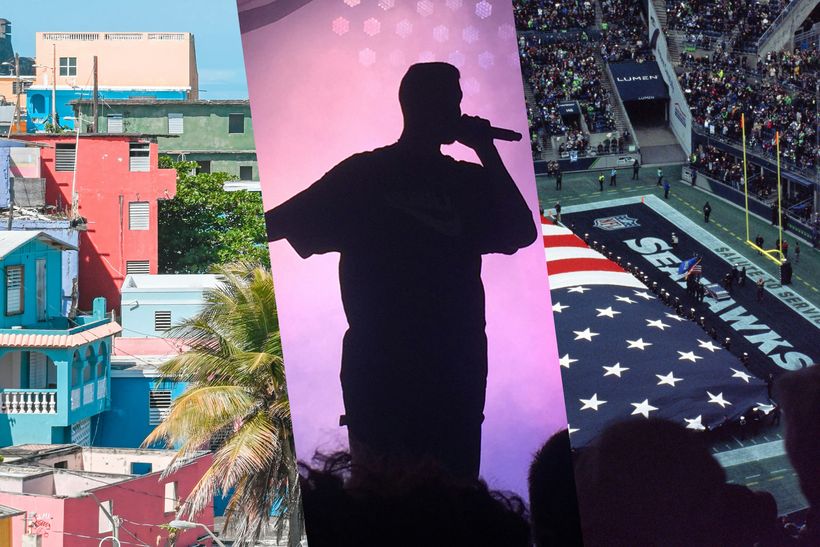

On February 8, 2026, 120 million-plus viewers worldwide are expected to tune into Super Bowl LX. However, the battle on the gridiron will be a secondary attraction for many, especially those from Puerto Rico and of Puerto Rican descent (colloquially known as "Boricuas"). Their attention will be focused on this year's halftime show, headlined by Bayamón-born rapper and producer Bad Bunny. Renowned for songs like "Yo Perreo Sola," "La Canción" and "Me Porto Bonito," the pop sensation is expected to bring a distinctive Latin American flair to his set, representing Puerto Rican culture and creativity to an audience unlike any other. Héctor Varela Rios, PhD, the Raquel and Alfonso Martínez-Fonts Endowed Assistant Professor in Latin American Studies at Villanova University, specializes in popular culture and writes extensively on the Boricua community, to which he himself belongs. From his perspective, Bad Bunny's upcoming performance in the Super Bowl halftime show marks "a high point for Puerto Rican pride," both within the U.S. territory and across the globe. "He is not the first Super Bowl performer to claim Puerto Rican ancestry—Jennifer Lopez performed alongside Colombia-born Shakira in 2020—but he is the first island-born Puerto Rican to perform," says Dr. Varela Rios. "At this moment, he is our brightest superstar and absolutely adored throughout Latin America and the world." To the professor's point, Bad Bunny is among the most successful musical acts touring today, having notched more than 7 million records sold, four diamond plaques and 11 platinums all before the age of 32. His popularity has not come at the expense of his art, either, with the rapper having won six Grammy Awards over the course of his career—including three for his latest album, "Debí Tirar Más Fotos." According to Dr. Varela Rios, Bad Bunny's widespread appeal and critical acclaim can be traced to his authenticity, courage and swagger. Singing in Spanish, making deep-cut cultural references and broaching sensitive, seemingly taboo topics, the Latin American pop star has effectively built a following by unabashedly embracing his own identity. (Perhaps tellingly, he titled his second album "Yo Hago Lo Que Me Da La," or "I Do Whatever I Want.") "Bad Bunny is proud of his Caribbean roots and keenly aware of the history of Puerto Rico, which influences his work," says Dr. Varela Rios. "In addition, he is very unapologetic about the content of his lyrics and performing style. It goes beyond mere shock with him; he relishes challenging assumptions of what being an artist should be, or needs to be in order to 'sell records.'" While this daring approach has netted Bad Bunny a number of accolades and a devoted legion of fans, it has not been without its share of detractors. Still, on the biggest stages and under the brightest lights, the celebrated artist has shown no inclination to alter or tone down his act. Dr. Varela Rios predicts the pop star's Super Bowl appearance will be no different. "Bad Bunny is a businessman, and one of the best I've ever seen," he adds. "This is an artist who knows what to do and how to do it, and when the Super Bowl halftime show's lights go down, his performance will certainly be remembered."