You might also like...

Check out some other posts from Villanova University

When individuals sign up for direct-to-consumer genetic testing, the extent to which they ever think about their genetic data is likely in the context of the service for which they paid: information on predisposition to a genetic illness, or confirmation of an ethnic background, for example.

But that data doesn’t just sit on a shelf, and while the most mainstream concern for such services is the privacy of your data, there is also the question of what else the companies do with it, and how.

Ana Santos Rutschman, SJD, LLM, professor and faculty director of the Health Innovation Lab at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law, is particularly interested in the latter. In June 2025, she co-authored an amicus brief centered on data protection and patient’s interests amid genetic testing company 23andMe’s bankruptcy proceedings. In December, many of those same co-authors published a paper in Nature Genetics, highlighting 23andMe’s bankruptcy as “an inflection point for the direct-to-consumer genetics market,” especially as it pertains to the broader corporate use of individuals’ scientific data.

The reason?

“How that data is used all depends on the policies of the individual companies,” she said.

Genetic Testing Companies Use Your Data For More Than The Services You Pay For Those who utilize genetic testing companies—for any reason—are likely also consenting, often unknowingly, to other unrelated items. This includes acknowledgment of information related to how your data might be further used or monetized.

“Most people don't think about secondary and tertiary uses of their data,” said Professor Rutschman. “[What they consent to] is displayed on the website somewhere, but it’s not easily understandable and accessible. It’s fine print.”

Such companies often operate beyond the traditional “fee for a service” relationship with consumers. Yes, they will give you the information you paid for—finding out whether you have German ancestry or are predisposed to certain genetic disease—but instead of that genetic data just being stored somewhere, it’s often sold for research purposes.

Today, in the age of AI big data, that might look something like this: The company puts your data in a box with parameters, along with thousands of others. Perhaps they are then able to observe a pattern that, until all that data was compiled, was previously unknown. They come up with a diagnostic or a medicine and patent it. That patent is licensed to somebody else, and the company makes money on the product.

The use of that data for scientific purposes—even ones that turn a profit— is not problematic in itself, says Professor Rutschman.

“Some people may even choose a company that allows scientific research over one that doesn’t. Many people may not care, but some will. The uses are not common knowledge, and that is worrisome. The public should be well-informed about what’s happening.”

Deeper problems may arise when they aren’t informed of those potential uses of their data. Professor Rutschman cited the infamous Henrietta Lacks case, in which Lacks’ cells were, and continue to be, one of the most valuable cell lines in cancer research. Neither Lacks nor her family were paid for the widespread use of her genetic material until a settlement was reached long after her death.

“When you have biologics involved, a concern is that if you have something potentially valuable, you may not see any money from it.”

Bankruptcy Can Cause Policy Upheaval To understand the role bankruptcy can play in all of this, one needs to refer back to the power of individual company policy in this space. There are no external laws that dictate how these companies can further monetize their data, says Professor Rutschman, as long as they don’t violate other laws, such as privacy laws.

That means that when a company like 23andMe goes bankrupt, as was the case in 2025, new ownership could enact completely different corporate policies for use of their property. In their specific case, the company was essentially bought back by 23andMe founder and CEO Anne Wojcicki’s non-profit, all but ensuring policies would remain the same. But that is exactly why Professor Rutschman and others are highlighting this specific case.

“Bankruptcy is bad in the sense that there's a lot of uncertainty,” she said. “In this instance, the person coming in was the person who was there before, so the policy is likely to continue. But that's very rare. There are a roster of companies with access to biological materials. 23andMe is a good example of something not going horribly wrong, but with the understanding that it absolutely could.”

Ways in which that could happen could be new ownership undermining the original intent of the data use by cessation of the company’s previous policies, or charging exorbitant prices to other entities to use that data for scientific research.

“Because there is no law, these new owners can essentially do as they please with their proprietary data, unless they do something incredibly careless that amounts to the level of illegal,” Professor Rutschman said. “And that is concerning.”

Onus Falls to Companies to Enact Safeguards To ensure a worst-case scenario for such companies does not unfold in a bankruptcy situation, Professor Rutschman points to a number of safeguards they could enact to protect their original commitments, ensure equitable access to data for scientific research and promote fair trade.

One of which is implementing a company policy stating that commitments from a previous iteration of the company need to be honored if ownership is transferred. Those could include, as the authors recommend, policies “honoring original research-oriented commitments under which the data were collected,” as well as not “enclosing the dataset for exclusive commercial use.”

She also highlights the need for Fair, Reasonable, and Non-Discriminatory (FRAND) voluntary licensing commitments, which are inherently more science and market friendly.

“Companies in many sectors have committed to this approach, and we are saying it should apply in this space as well. You’ll charge your royalty, but it can’t be a billion dollars for a data set, nor would it be done by exclusively selling to one entity. You can get that billion dollars by selling to 15, 50 or 100 companies, and from a scientific research perspective, that’s what we want. Otherwise, you have a monopoly or duopoly.

“There are a lot of different models that can be used, but ultimately what we are arguing is leaving this unaddressed is a really bad idea. It leaves everything exposed, and something bad is more likely to happen.”

On February 8, 2026, 120 million-plus viewers worldwide are expected to tune into Super Bowl LX. However, the battle on the gridiron will be a secondary attraction for many, especially those from Puerto Rico and of Puerto Rican descent (colloquially known as "Boricuas").

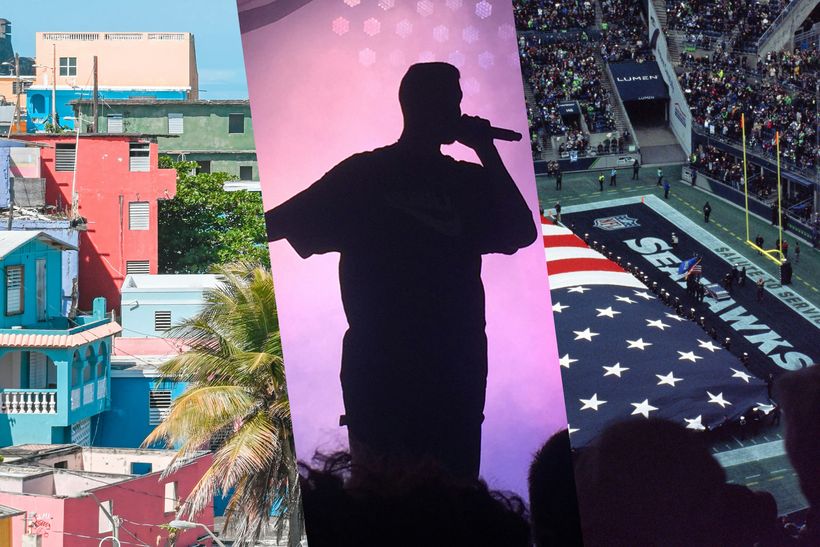

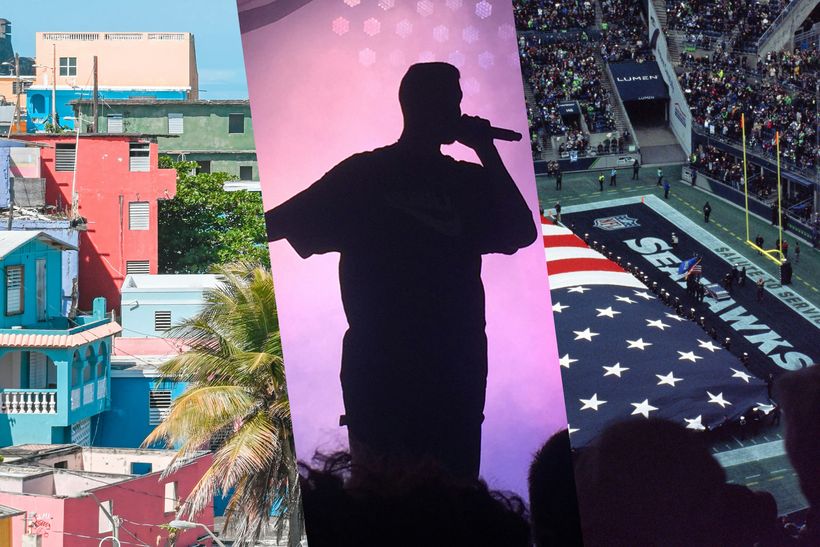

Their attention will be focused on this year's halftime show, headlined by Bayamón-born rapper and producer Bad Bunny. Renowned for songs like "Yo Perreo Sola," "La Canción" and "Me Porto Bonito," the pop sensation is expected to bring a distinctive Latin American flair to his set, representing Puerto Rican culture and creativity to an audience unlike any other.

Héctor Varela Rios, PhD, the Raquel and Alfonso Martínez-Fonts Endowed Assistant Professor in Latin American Studies at Villanova University, specializes in popular culture and writes extensively on the Boricua community, to which he himself belongs. From his perspective, Bad Bunny's upcoming performance in the Super Bowl halftime show marks "a high point for Puerto Rican pride," both within the U.S. territory and across the globe.

"He is not the first Super Bowl performer to claim Puerto Rican ancestry—Jennifer Lopez performed alongside Colombia-born Shakira in 2020—but he is the first island-born Puerto Rican to perform," says Dr. Varela Rios. "At this moment, he is our brightest superstar and absolutely adored throughout Latin America and the world."

To the professor's point, Bad Bunny is among the most successful musical acts touring today, having notched more than 7 million records sold, four diamond plaques and 11 platinums all before the age of 32. His popularity has not come at the expense of his art, either, with the rapper having won six Grammy Awards over the course of his career—including three for his latest album, "Debí Tirar Más Fotos."

According to Dr. Varela Rios, Bad Bunny's widespread appeal and critical acclaim can be traced to his authenticity, courage and swagger. Singing in Spanish, making deep-cut cultural references and broaching sensitive, seemingly taboo topics, the Latin American pop star has effectively built a following by unabashedly embracing his own identity. (Perhaps tellingly, he titled his second album "Yo Hago Lo Que Me Da La," or "I Do Whatever I Want.")

"Bad Bunny is proud of his Caribbean roots and keenly aware of the history of Puerto Rico, which influences his work," says Dr. Varela Rios. "In addition, he is very unapologetic about the content of his lyrics and performing style. It goes beyond mere shock with him; he relishes challenging assumptions of what being an artist should be, or needs to be in order to 'sell records.'"

While this daring approach has netted Bad Bunny a number of accolades and a devoted legion of fans, it has not been without its share of detractors. Still, on the biggest stages and under the brightest lights, the celebrated artist has shown no inclination to alter or tone down his act. Dr. Varela Rios predicts the pop star's Super Bowl appearance will be no different.

"Bad Bunny is a businessman, and one of the best I've ever seen," he adds. "This is an artist who knows what to do and how to do it, and when the Super Bowl halftime show's lights go down, his performance will certainly be remembered."

Long proclaimed Italy’s “moral capital,” Milan is renowned worldwide for its significant contributions to fashion, design and the arts. Soon, another point of pride will be added to the city’s storied history, when the regional hub—and partnering town Cortina d’Ampezzo—plays host to the 2026 Winter Olympics in February.

Luca Cottini, PhD, is a professor of Italian Studies and an expert on the evolution of Italian culture, particularly through the 19th and 20th centuries. Recently, he shared some thoughts concerning Milan and Cortina’s successful joint bid for the Olympics, the themes and iconography expected to define this year’s opening ceremony and the symbolic significance of Italy’s selection as a host nation.

Question: What was the role of past major events in Milan and Cortina—like the 2015 World’s Fair and the 1956 Winter Olympics—in helping to elevate their appeal for these games? Luca Cottini: I’ll start by saying that although people notice world’s fairs less than the Olympics, they are more impactful to a city and country because they generate more revenue, business, political relationships and positive reputation. They are events in which all the world comes together and each country exposes its excellence, while the host nation brings a visibility that it would not carry otherwise. In 2015, Milan hosted the world’s fair, which generated a completely new fairgrounds area and a visibility of politics, industry, technology and modernity in a way that brings the city to a global stage. I would say that is when the ascent of Milan really started, especially as a desirable destination.

With Cortina, after the 2015 World’s Fair—and especially after the COVID-19 pandemic—the Dolomites became really a popular region for travelers to visit. Cortina is also symbolic to Olympic history, because it's the site of the first Olympics that took place in Italy, in 1956 during the reconstruction era. That was the Dolce Vita period, in the middle of the 1950s economic boom, and those games were followed by Rome’s Summer Olympics in 1960. They both represented a way in which Italy, coming out of the war destroyed, was reaffirming its rebirth.

Over the years, fewer cities have wanted to host the Olympics because they tend to carry a lot of economic burden, financial debt and little return on investment. In this sense, Milan and Cortina, helped by increased popularity after the world’s fair, sold themselves as a sustainable Olympics. Ninety percent of the buildings were refurbished from older buildings, and they will serve purposes after the Olympics. It’s difficult to tell whether it’s economically sound or not, but it is a way to promote two cities that are in big moments of growth.

Q: These Olympic Games will be celebrating Milan’s contributions to fashion. What is the city’s significance to the fashion world? LC: Milan is certainly the capital of fashion in Italy, and is one of the capitals of fashion in the world, along with Paris, New York and London. The fashion heritage that the city carries now in iconic brands like Armani, Versace, Moschino and Dolce & Gabbana is the outcome of a process that took shape in the late 1970s. Until then, fashion in Italy was mainly related to Rome, through cinema, and Florence, as that city represented a new Renaissance in the postwar years. But in the 1970s, much of this fashion world moved from those cities to Milan, because there was a conglomeration of labor, skills, capital and creativity that generated a complex productive and cultural system, or the so-called “Sistema Moda.” This is a particular approach to the industry in Italy that coordinates management and creativity around the figures of a big creative director and a big manager who work together in creating not just nice styles, but also sustainable outlets and markets in and outside Italy.

In turn, with its reputation, Milan gives the Olympics that seal of grandeur and coolness. The connection with fashion and promotion of uniqueness is part of the national rhetoric that surrounds what we call “Made in Italy,” this idea of luxury, styling, beauty, order and measure that is endowed in the Italian DNA.

Q: Andrea Bocelli—who also appeared in Torino’s 2006 closing ceremony—is supposed to sing once again in this year’s opening ceremony. Aside from his popularity, what is the symbolic significance of his selection as a performer? LC: Bocelli is an interesting case. He is a prototypical Italian success story, which is born in the peninsula but is then ratified outside of Italy. As Bocelli became a global sensation in the U.S., he then came back to his roots in Italy, where his voice has become a symbol of national unity, as epitomized in his solo concerto of Milan, during the pandemic, when he sang in front of the empty Piazza del Duomo, facing the city’s cathedral. In his Catholic faith and secular operatic repertoire, he symbolizes Italian culture as a similar piazza or open space where different voices can converge in a temperate balance. When you put together Bocelli, Mariah Carey and whoever else will be part of the ceremony, that same Italian identity will give rise to a new synthesis, as the encounter of tradition and novelty, grounded-ness and openness.

Q: The Olympic flames are supposed to be lit in two cauldrons—one in Milan and one in Cortina—each with a design inspired by Leonardo da Vinci. What was da Vinci’s importance to Milan, specifically? LC: Da Vinci is part of the fabric of Milan. He spent 20 years in the city, painting “The Last Supper” and working at Castello Sforzesco, as well as many other places. His footprint is all over Milan, in its design, walls, canal system and more. He is an archetype of the Italian mind in as much as it represents the combination of engineering and beauty. The word Ingenium in Latin, meaning “genius,” overflows in English into the word “engineering” and also “ingenuity,” which reflects the creative mind. Da Vinci represents the synthesis of Italian Ingenium as a combination of aesthetics and problem solving, which you still see in the city today.