3 min

ExpertSpotlight: Why the Strait of Hormuz Matters: The World’s Most Critical Chokepoint

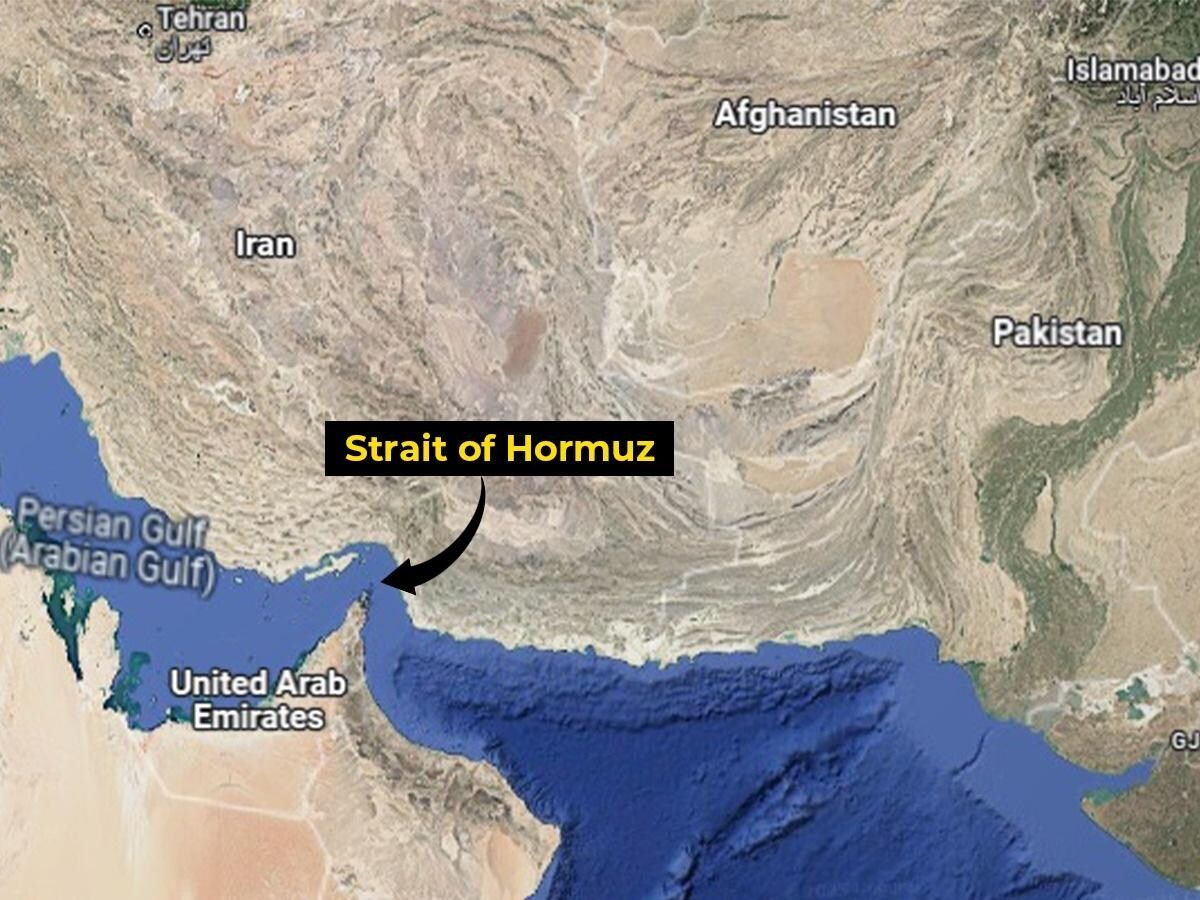

The Strait of Hormuz is one of the most strategically vital waterways on Earth. Just 20 miles wide at its narrowest point, with shipping lanes only a few miles across in each direction, this narrow channel connects the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea. Through it flows roughly one-fifth of the world’s petroleum supply, along with vast quantities of liquefied natural gas, particularly from Qatar. For global markets, the Strait is more than geography, it is a pressure point. Any disruption, even the threat of one, can send oil prices surging and rattle financial markets worldwide. A History Shaped by Empire and Energy For centuries, the Strait served as a maritime corridor linking Mesopotamia, Persia, India, and East Africa. Control over it shifted between regional powers, colonial empires, and eventually modern nation-states. In the 16th century, the Portuguese seized nearby islands to dominate regional trade routes. Later, British naval power asserted influence during the height of imperial shipping dominance. In the 20th century, however, the Strait’s importance expanded dramatically with the rise of oil exports from Gulf states. After the 1979 Iranian Revolution, tensions surrounding the Strait intensified. During the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, particularly the so-called “Tanker War” phase, commercial vessels were targeted, highlighting how vulnerable global energy supplies could be. Since then, periodic confrontations between Iran, the United States, and regional powers have kept the Strait at the centre of geopolitical risk. Why It Is So Important Today 1. Energy Security Major oil producers including Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE, Kuwait, and Qatar rely heavily on this route. Even short-term closures could disrupt millions of barrels per day in global supply. 2. Global Economic Stability Because oil is globally traded and priced, disruptions in the Strait impact fuel costs, inflation, shipping, and consumer prices worldwide — including in North America and Europe. 3. Military Strategy The Strait is bordered primarily by Iran to the north and Oman to the south. Iran has periodically threatened to close the passage in response to sanctions or military pressure. The U.S. Navy and allied forces maintain a consistent presence to ensure freedom of navigation. 4. Modern Geopolitical Flashpoint Recent decades have seen drone seizures, tanker detentions, and naval standoffs. Each incident reinforces how fragile global energy logistics can be when concentrated in a single corridor. The Strait as a Symbol of Interdependence The Strait of Hormuz underscores a central truth of globalization: the world’s economies are deeply interconnected and geographically vulnerable. A narrow stretch of water in the Middle East can influence gasoline prices in Ontario, manufacturing costs in Germany, and energy security debates in Asia. It is both a trade artery and a geopolitical lever — a reminder that geography still shapes global power. Expert Angles for Media An expert in geopolitics, energy economics, or maritime security could explore: How vulnerable is the global economy to a prolonged closure? Can alternative pipelines realistically replace Hormuz traffic? What role do regional alliances play in deterring conflict? How does the Strait shape Iran’s negotiating power? What would insurance and shipping markets do in a crisis? The Strait of Hormuz is not simply a map feature — it is one of the world’s most consequential strategic chokepoints. Its stability underpins global energy flows, economic predictability, and international security. If tensions rise there, the world feels it. Our experts can help! Connect with more experts here: www.expertfile.com