Experts Matter. Find Yours.

Connect for media, speaking, professional opportunities & more.

UConn's Amanda J. Crawford on one Sandy Hook family's 'epic fight'

Since December 14, 2012, the families of 18 children and six adults murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary School have been forced to live amidst a tidal wave of conspiracy theorists and their constant lies, threats, and harassment. As lawsuits challenging some of the most vocal purveyors of that misinformation are working through the court system, the stories of the hardships faced by some of these families -- endured while they have tried to grieve their unimaginable loss -- have brought new attention to the profound and negative effects that the wildfire spread of misinformation has on the lives of the people most impacted. Amanda J. Crawford, an assistant professor with the UConn Department of Journalism who studies misinformation and conspiracy theories, offers the story of one family in an in-depth and heartbreaking, but critically important, story for the Boston Globe Magazine: Lenny knew online chatter about the shadow government or some such conspiracy was all but inevitable. When a neuroscience graduate student killed 12 and injured dozens of moviegoers with a semiautomatic assault rifle in Aurora in July, five months prior, there had been allegations about government mind control. When Lenny searched his son’s name in early January 2013, he was disgusted at the speculation about the shooting. People called it a false flag. Mistakes in news coverage had become “anomalies” that conspiracy theorists claimed as proof of a coverup. Why did the shooter’s name change? Why did the guns keep changing? Press conferences were analyzed for clues. Vance’s threat to prosecute purveyors of misinformation was taken as an indication they were onto something. But what concerned Lenny most was their callous scrutiny of the victims and their families. Some people claimed a photo of a victim’s little sister with Obama really showed the dead girl still alive. Others speculated the murdered children never existed at all. They called parents and other relatives “crisis actors” paid to perform a tragedy. And yet, they also criticized them for not performing their grief well enough. There were even claims specifically about Veronique. Lenny needed to warn her. “There are some really dark, twisted people out there calling this a hoax,” he told her. Veronique didn’t understand. There was so much news coverage, so many witnesses. “How could that possibly be?” “If you put yourself out there, people will question your story,” Lenny cautioned. Veronique thought he must be exaggerating a few comments from a dark corner of the Web. This can’t possibly gain traction, she thought. No, no, no! Truth matters. If I tell my story, people will be able to see that I am a mother who is grieving. Amanda J. Crawford is a veteran political reporter, literary journalist, and expert in journalism ethics, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and the First Amendment. Click on her icon now to arrange an interview with her today.

Are You an Expert? Here’s How to Tell

Have you ever wondered whether or not you are an expert? When asked this question about what defines expertise, you will hear a variety of answers. Many will reference key requirements such as an expert must have extensive knowledge in their field. Others will see education, published work, or years of experience as key qualifiers. Yet there are so many other dimensions of expertise that contribute to how visible, influential and authoritative they are within their community of practice or with the general public. Who Qualifies as an Expert? I started looking closer at this topic for two reasons. The first is my personal work with experts. Having worked with thousands of them across a variety of sectors I've observed that many are driven to develop themselves professionally as an expert to meet a variety of objectives. Often these are focused on raising one's profile and reputation among peers or with the broader market to inform the public. Some see media coverage being an essential part of their strategy while others are more interested in developing a larger audience for their research or client work, by speaking at conferences or on podcasts. Others have a focus on improving their PageRank on search engines. All these activities can enable important objectives such as attracting new clients, research funding or talent. The second reason for this deeper dive into expertise is a need to better organize how we look at experts within organizations. My work with communications departments in knowledge-based sectors reveals that they are keen to learn more about how they can better engage their experts to build reputation, relationships and revenue. However, better engagement starts with a better understanding of what qualifies someone as an expert - what attributes can we objectively look at that define expertise? With that knowledge, we can first better appreciate the amount of work experts have put into establishing themselves in their field. Then organizations can nurture this expertise in a more collaborative way to accomplish shared goals. My observation is that with a little more insight, empathy, and alignment, both experts and their organizations can accomplish incredible things together. And there has never been a more important time for experts to "show their smarts." By definition, an expert is someone with comprehensive or authoritative knowledge in a particular area of study. While formal education and certifications are a starting point for expertise, many disciplines don’t have a set list of criteria to measure expertise against. It’s also important to recognize other dimensions of expertise that relate not just to the working proficiency in a field but also to the degree of influence and authority they have earned within their profession or community of practice. Because of this, expertise is often looked at as a person’s cumulative training, skills, research and experience. What are the Key Attributes of Expertise? In evaluating your accomplishments and the various ways you can contribute as an expert to both your community of practice and the public, here are some key questions that can help you assess how you are developing your expertise: Have you completed any formal education or gained relevant experience to achieve proficiency in your chosen field? Are you actively building knowledge in a specific discipline or practice area by providing your services as an expert? Are you generating unique insights through your research or fieldwork? Are you publishing your work to establish your reputation and reach a broader audience such as publications or books? Are you teaching in the classroom or educating and inspiring audiences through speaking at conferences? Do you demonstrate a commitment to impact your community of practice and help advance your field and generate an impact on society by informing the public? Have you established a reputation as a go-to source for well-informed, unique perspectives? Some Additional Tips to Help you Develop Your Expertise To further the discussion, I’ve also shared further thoughts about the meaning of “expertise”. As you think about developing your own personal skills, or if you are a communicator who is responsible for engaging with your organizations experts, here are a few additional principles to keep in mind. Experts Aren't Focused on Some“Magic Number” Related to Hours of Experience Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers” (2008), outlined the now famous “10,000-hour rule” as the magic number of greatness for the time it takes to master a given field. As the rule goes, you could become a genuine expert in a field with approximately 10,000 hours of practice — roughly 3 hours a day, every day for a consecutive decade. But is that what it really takes to become an expert? But is that what it really takes to become an expert? Or did Gladwell oversimplify the concept of expertise? Some of his assumptions for “Outliers” (which became a major bestseller) relied on research from Dr. Anders Ericsson at Florida State University who made expertise the focus of his research career. Contrary to how Gladwell outlined it, Ericsson argued that the way a person practised mattered just as much, if not more, than the amount of time they committed to their discipline. It also depends on the field of research or practice one is involved in. Some disciplines take decades to achieve expertise and many experts will admit they are just scratching the surface of what they are studying, well after they have passed the 10,000-hour mark. That might be just the first stage of proficiency for some disciplines. Experts are Continuously Learning It’s difficult to claim proficiency as an expert if you are not staying current in your field. The best experts are constantly scouring new research and best practices. Dr. Anders Ericsson observed in his work that "deliberate practice" is an essential element of expertise. His reasoning was that one simply won’t progress as an expert unless they push their limits. Many experts aren’t satisfied unless they are going beyond their comfort zone, opening up new pathways of research, focusing on their weaknesses, and broadening their knowledge and skills through avenues such as peer review, speaking, and teaching. The deliberate practice occurred “at the edge of one’s comfort zone” and involved setting specific goals, focusing on technique, and obtaining immediate feedback from a teacher or mentor. Experts Apply their Knowledge to Share Unique Perspectives While many experts conduct research, simply reciting facts isn't enough. Those who can provide evidence-based perspectives, that objectively accommodate and adapt to new information will have more impact. Expertise is also about developing unique, informed perspectives that challenge the status quo, which can at times be controversial. Experts know that things change. But they don’t get caught up in every small detail in ways that prevent them from seeing the whole picture. They don't immediately rush toward new ideas. They consider historical perspectives and patterns learned from their research that provide more context for what's happening today. And these experts have the patience and wisdom to validate their perspectives with real evidence. That's why expert sources are so valuable for journalists when they research stories. The perspectives they offer are critical to countering the misinformation and uninformed opinions found on social media. Experts Connect with a Broader Audience Many experts are pushing past traditional communication formats, using more creative and visual ways to translate their research into a wider audience. We conducted research with academics in North America and in Europe who are trying to balance their research (seen in traditional peer-reviewed journals) with other work such as blogs, social media, podcasts and conferences such as TEDx - all with the goal to bring their work to a wider audience. While that's an essential part of public service, it pays dividends for the expert and the organization they represent. Experts Are Transparent More than ever, credible experts are in demand. The reason for this is simple. They inspire trust. And the overnight success some have seemingly achieved has come from decades of work in the trenches. They have a proven record that is on display and they make it easy to understand how they got there. They don't mask their credentials or their affiliations as they didn't take shortcuts. They understand that transparency is a critical part of being seen as credible. Experts Don’t Take “Fake It Till You Make It” Shortcuts The phrase “fake it till you make it,” is a personal development mantra that speaks to how one can imitate confidence, competence, and an optimistic mindset, and realize those qualities in real life. While this pop psychology construct can be helpful for inspiring personal development, it gets problematic when it becomes a strategy for garnering trust with a broader audience to establish some degree of authority - especially when this inexperience causes harm to others who may be influenced by what they see. When self-appointed experts take shortcuts, promoting themselves as authorities on social media without the requisite research or experience, this blurs the lines of expertise and erodes the public trust. Experts Are Generous The best experts are excited about the future of their field, and that translates to helping others become experts too. That's why many openly share their valuable time, through speaking, teaching and mentorship. In the end, they understand that these activities are essential to developing the scale and momentum necessary to tackle the important issues of the day. How Do You Show your Smarts? How do you personally score on this framework? Or if you are in a corporate communications or academic affairs role in an institution how does this help you better understand your experts so you can better develop your internal talent and build your organization’s reputation? As always we welcome your comments as we further refine this and other models related to expertise. Let us know what you think. Helpful Resources Download our Academic Experts and the Media (PDF) This report, based on detailed interviews with some of the most media-experienced academics across the UK and United States draws on their experiences to identify lessons they can share in encouraging other academics to follow in their path. Download the UK Report Here Download the US Report Here The Complete Guide to Expertise Marketing for Higher Education (PDF) Expertise Marketing is the next evolution of content marketing. Build value by mobilizing the hidden people, knowledge and content you already have at your fingertips. This win-win solution not only gives audiences better quality content, but it also lets higher ed organizations show off their smarts. Download Your Copy

Under new ownership - what's next for Twitter and the social media landscape

He said he'd do it - and he did. Billionaire, innovator and always the controversial CEO, Elon Musk scratched together over 40 billion dollars and has taken the reigns of social media giant Twitter. But now that thew deed is done - a lot of people have some concerns about Musk's intentions for the platform and its hundreds of thousands of users. Will there be an edit button? Will there finally be an end to 'bots'? And what about moderation and free speech? These are all valid and important questions to ask, and that's why Michigan State University's Anjana Susarla penned a recent piece in The Conversation to tackle those topics. What lies ahead for Twitter will have people talking and reporters covering for the days and weeks to come. And if you're a journalist looking for insight and expert opinion - then let us help with your stories. Anjana Susarla is the Omura Saxena Professor of Responsible AI at Michigan State University. She's available to speak with media, simply click on her icon now to arrange an interview today.

Journalism, Libel, and Political Messaging in America - UConn's Expert Weighs in

Former Alaska governor and vice presidential candidate Sarah Palin didn't cause the deadly 2011 shooting in Tuscon, Arizona, that injured Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, says former journalist and UConn expert Amanda Crawford in a new essay for Nieman Reports. Palin is asking for a new trial after a jury in February rejected her libel lawsuit against the New York Times. Palin sued the newspaper after it published a 2017 editorial that erroneously claimed she was responsible for the shooting. The Times quickly issued a correction. But Crawford says that, in her opinion, Palin has contributed to increased vitriol in American politics today, and that libel laws protecting freedom of the press need to be guarded: Palin, the 2008 Republican vice presidential nominee known for her gun-toting right-wing invective, is now asking for a new trial in the case that hinges on an error in a 2017 Times editorial, “America’s Lethal Politics.” The piece, which bemoaned the viciousness of political discourse and pondered links to acts of violence, was published after a man who had supported Sen. Bernie Sanders opened fire at congressional Republicans’ baseball practice, injuring House Majority Whip Steve Scalise. The Times editorial noted that Palin’s political action committee published a campaign map in 2010 that used a graphic resembling the crosshairs of a rifle’s scope to mark targeted districts. It incorrectly drew a link between the map and the shooting of Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, the Democratic incumbent in one of those districts, while she was at a constituent event in a grocery store parking lot in Tucson less than a year later. I was a political reporter in Arizona at the time, and I remember how Giffords herself had warned that the map could incite violence. “We’re on Sarah Palin’s targeted list,” she said in a 2010 interview, according to The Washington Post, “but the thing is that the way that she has it depicted has the crosshairs of a gun sight over our district, and when people do that, they’ve got to realize there are consequences to that action.” In the wake of the mass shooting in Tucson, some officials and members of the media suggested that political rhetoric, including Palin’s, may be to blame. In fact, no link between the campaign map and the shooting was ever established. As the judge said, the shooter’s own mental illness was to blame. That is where the Times blundered. An editor inserted language that said, “the link to political incitement was clear.” (The Times promptly issued a correction.) This was an egregious mistake and the product of sloppy journalism, but both the judge and the jury agreed that it was not done with actual malice or reckless disregard for the truth. That’s the standard that a public figure like Palin must meet because of the precedent set in the Sullivan case and subsequent decisions. Even if Palin is granted a new trial and loses again, she is likely to appeal. Her lawsuit is part of a concerted effort by critics of the “lamestream media,” including former President Donald Trump, to change the libel standard to make it easier for political figures to sue journalists and win judgments for unintentional mistakes. They want to inhibit free debate and make it harder for journalists to hold them accountable. -- Nieman Reports, March 14, 2022 If you are a reporter who is interested in covering this topic, or who would like to discuss the intersection between politics and media, let us help. Amanda Crawford is a veteran political reporter, literary journalist, and expert in journalism ethics, misinformation, conspiracy theories, and the First Amendment. Click on her icon now to arrange an interview today.

State-sponsored computational propaganda is a potential threat during the 2022 Winter Olympics

Sagar Samtani, assistant professor and Grant Thornton Scholar, whose research centers on AI for cybersecurity and cyber threat intelligence, is particularly watching two major cybersecurity issues during the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing Feb. 4-20. “The Olympics are an international, global event. As such, there are often political undertones and agendas that may drive how countries present themselves. Disinformation, misinformation, and computational propaganda that are state-sponsored or provided by individual threat actors could pose a significant threat,” Samtani said. Samtani noted that this will be biggest Olympics for streaming services. For example, NBC Universal will present Winter Olympics record of over 2,800 hours of coverage. But this move away from network reliance on broadcast channels could present a tantalizing target for hackers. “The Olympics are a widely covered, highly publicized TV event. In recent years, streaming services have grown in popularity, while conventional satellite and cable services have declined. As such, the concerns around denial-of-service attacks against prevailing streaming services as it pertains to viewing the Olympics is a very real concern,” he said. Samtani can be reached at ssamtani@iu.edu

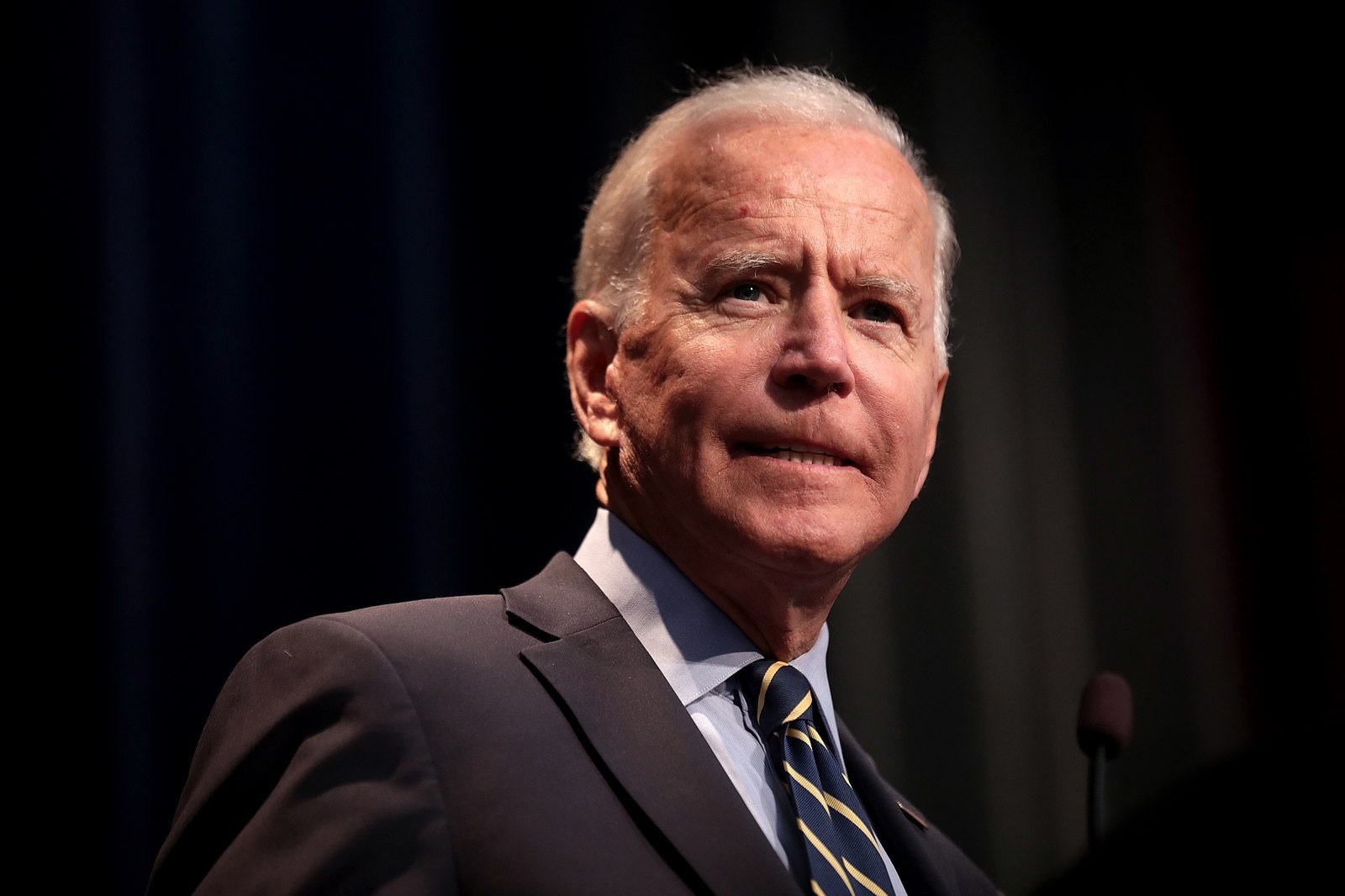

Will Biden’s Plan to Resettle Afghans Transform the U.S. Refugee Program?

Among the high-profile anti-immigration policies that characterized the four years of Donald Trump’s presidency was a dramatic contraction in refugee resettlement in the United States. President Biden has expressed support for restoring U.S. leadership, and increased commitment is needed to help support the more than 80 million people worldwide displaced by political violence, persecution, and climate change, says UConn expert Kathryn Libal. As Libal writes, with co-author and fellow UConn professor Scott Harding, in a recent article for the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, the rapid evacuation of more than 60,000 Afghans pushed the Biden administration to innovate by expanding community-based refugee resettlement and creating a private sponsorship program. But more resources are needed to support programs that were severely undermined in previous years and to support community-based programs that help refugees through the resettlement process: Community sponsorship also encourages local residents to “invest” in welcoming refugees. Under existing community sponsorship efforts, volunteers often have deep ties to their local communities—critical for helping refugees secure housing, and gain access to employment, education, and health care. As these programs expand, efforts to connect refugees to community institutions and stakeholders, which are crucial to help facilitate their social integration, may be enhanced. As Chris George, Executive Director of Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services in New Haven, Connecticut, has observed, “It’s better for the refugee family to have a community group working with them that knows the schools and knows where to shop and knows where the jobs are.” As more local communities take responsibility for sponsoring refugee families, the potential for a more durable resettlement program may be enhanced. In the face of heightened polarization of refugee and immigration policies, community sponsorship programs can also foster broad-based involvement in refugee resettlement. In turn, greater levels of community engagement can help challenge opposition toward and misinformation about refugees and create greater public support for the idea of refugee resettlement. Yet these efforts are also fraught with significant challenges. Sponsor circle members may have limited capacity or skills to navigate the social welfare system, access health care services, or secure affordable housing for refugees. If group members lack familiarity with the intricacies of US immigration law, helping Afghans designated as “humanitarian parolees” attain asylum status may prove daunting. Without adequate training and ongoing support from resettlement agencies and caseworkers, community volunteers may experience “burn out” from these various responsibilities. Finally, “successful” private and community sponsorship efforts risk providing justification to the arguments of those in support of the privatization of the USRAP and who claim that the government’s role in resettlement should be limited. Opponents of refugee resettlement could argue that community groups are more effective than the existing public–private resettlement model and seek to cut federal funding and involvement in resettlement. Such action could ultimately limit the overall number of refugees the United States admits in the future. December 11 - Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. If you are a journalist looking to know more about this topic – then let us help with your coverage and questions. An associate professor of social work and human rights, Kathryn Libal is the director of UConn's Human Rights Institute and is an expert on human rights, refugee resettlement, and social welfare. She is available to speak with media – click on her icon now to arrange an interview.

Misinformation expert on YouTube ban on false information on vaccines

Lisa Fazio, associate professor of psychology and human development, is available for commentary on YouTube's ban on vaccine misinformation. Lisa is an expert in misinformation and false news, studying how people learn, interpret and remember information. She can speak to YouTube's history as a vector for misinformation and other points related to the topic, including: The importance of finding trusted sources and how it's even harder than normal to tell what is a reliable source, especially as so many personal accounts are floating around Misinformation and mixed messages sent from politicians and government officials on vaccine implications The dangers of so many "experts" talking publicly about vaccines, particularly around the periphery of their expertise and the damage that has been done, particularly during the pandemic

As America begins to stare down a fourth wave of COVID 19 – vaccine awareness and the debate about to get immunized or not is still a hot topic. And unfortunately, the level of misinformation being spread on social media is rampant. Recently, MSU’s Anjana Susarla the Omura Saxena Professor of Responsible AI was featured in The Conversation in a piece titled ‘Big tech has a vaccine misinformation problem – here’s what a social media expert recommends’ . It’s a very compelling read and must have information for anyone looking at the threat of fake news and how quickly it can spread. As well, the article also highlights tactics n blocking sites and mitigating the spread of misinformation. And if you are a journalist looking to know more about how big tech needs to keep up the fight against fake news – then let us help. Anjana Susarla is the Omura Saxena Professor of Responsible AI at Michigan State University. She's available to speak with media, simply click on her icon now to arrange an interview today.

First Commercial-Scale Wind Farm in the U.S. Would Generate Electricity to Power 400,000 Homes

The Vineyard Wind project, located off the coast of Massachusetts, is the first major offshore wind farm in the United States. It is part of a larger push to tackle climate change, with other offshore wind projects along the East Coast under federal review. The U.S. Department of the Interior has estimated that, by the end of the decade, 2,000 turbines could be along the coast, stretching from Massachusetts to North Carolina. "While the case for offshore wind power appears to be growing due to real concerns about global warming, there are still people who fight renewable energy projects based on speculation, misinformation, climate denial and 'not in my backyard' attitudes," says Karl F. Schmidt, a professor of practice in Villanova University's College of Engineering and director of the Resilient Innovation through Sustainable Engineering (RISE) Forum. "There is overwhelming scientific evidence that use of fossil fuels for power generation is driving unprecedented levels of CO2 into our atmosphere and oceans. This causes sea level rise, increasing ocean temperature and increasing ocean acidity, all which have numerous secondary environmental, economic and social impacts." Schmidt notes that what's often missing for large capital projects like the Vineyard Wind project is a life cycle assessment (LCA), which looks at environmental impacts throughout the entire life cycle of the project, i.e., from raw material extraction, manufacturing and construction through operation and maintenance and end of life. These impacts, in terms of tons/CO2 equivalent, can then be compared with the baseline—in this case, natural gas/coal power plants. "With this comprehensive look, I suspect the LCA for an offshore wind farm would be significantly less than a fossil fuel power plant," says Prof. Schmidt. Complementing the LCA should be a thorough, holistic view encompassing the pertinent social, technological, environmental, economic and political (STEEP) aspects of the project, notes Prof. Schmidt. "This would include all views of affected stakeholders, such as residents, fishermen, local officials and labor markets. Quantifying these interdependent aspects can lead to a more informed and balanced decision-making process based on facts and data." "At Villanova's Sustainable Engineering Department, we've successfully used both the LCA and STEEP processes... for many of our RISE Forum member companies' projects," notes Prof. Schmidt.

The Facebook Oversight Board’s ruling temporarily upholding the social media giant’s ban on former President Donald J. Trump, which they instructed the company to reassess within six months, noted that the parameters for an indefinite suspension are not defined in Facebook's policies. The non-decision in this high-profile case illustrates the difficulties stemming from the lack of clear frameworks for regulating social media. For starters, says web science pioneer James Hendler, social media companies need a better definition of the misinformation they seek curb. Absent a set of societally agreed upon rules, like those that define slander and libel, companies currently create and enforce their own policies — and the results have been mixed at best. “If Trump wants to sue to get his Facebook or Twitter account back, there’s no obvious legal framework. There’s nothing to say of the platform, ‘If it does X, Y, or Z, then it is violating the law,’” said Hendler, director of the Institute for Data Exploration and Applications at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. “If there were, Trump would have to prove in court that it doesn’t do X, Y, or Z, or Twitter would have to prove that it does, and we would have a way to adjudicate it.” As exemplified in disputes over the 2020 presidential election results, political polarization is inflamed by a proliferation of online misinformation. A co-author of the seminal 2006 Science article that established the concept of web science, Hendler said that “as society wrestles with the social, ethical, and legal questions surrounding misinformation and social media regulation, it needs technologist to help inform this debate.” “People are claiming artificial intelligence will handle this, but computers and AI are very bad at ‘I’ll know it when I see it,’” said Hendler, who’s most recent book is titled Social Machines: The Coming Collision of Artificial Intelligence, Social Networking, and Humanity. “What we need is a framework that makes it much clearer: What are we looking for? What happens when we find it? And who’s responsible?” The legal restrictions on social media companies are largely dictated by a single sentence in the Communications Decency Act of 1996, known as Section 230, which establishes that internet providers and services will not be treated as traditional publishers, and thus are not legally responsible for much of the content they link to. According to Hendler, this clause no longer adequately addresses the scale and scope of power these companies currently wield. “Social media companies provide a podium with an international reach of hundreds of millions of people. Just because social media companies are legally considered content providers rather than publishers, it doesn’t mean they’re not responsible for anything on their site,” Hendler said. “What counts as damaging misinformation? With individuals and publishers, we answer that question all the time with libel and slander laws. But what we don’t have is a corresponding set of principles to adjudicate harm through social media.” Hendler has extensive experience in policy and advisory positions that consider aspects of artificial intelligence, cybersecurity and internet and web technologies as they impact issues such as regulation of social media, and powerful technologies including facial recognition and artificial intelligence. Hendler is available to speak to diverse aspects of policies related to social media, information technologies, and AI.